If you have a child who struggles with sad stories…a child who gets really uncomfortable when bad things happen and wants you to stop reading (or wants to stop reading themselves)… then this episode is for you.

And actually, it’s for them, too! In fact, it’s an episode you might like to listen to with your kids.

In this episode, you’ll hear:

- What to do if your kids get upset while reading sad stories

- Why you can predict what terrible thing might be coming (and when in the story it’ll happen)

- What the author is doing and why

- How to help your kids hang on to the story, and get all the way through to the hope

Click the play button below or scroll down to keep reading.

The Tent Poles Holding Up the Story

Have you ever been camping? Maybe you’ve slept in a tent?

There are many different shapes of tents: A-frame tents, domes, tunnels, cabins. They are different shapes, different sizes, and different colors.

Even though they are all different, those tents have a few things in common. They all:

- Provide shelter

- Consist of some kind of fabric that makes up the walls, ceiling, and floor

- Need poles or some kind of structure to hold them aloft

Tents are held up by poles. And stories are held up by a structure too.

Today I want to show you the poles that are holding up many stories and how they can help us understand what authors are doing doing in sad and scary stories.

We can think of stories kind of like tents.

Stories, too, come in all shapes and sizes and are all different from one another.

But they all have a few things in common, too. They all have characters, for example. And those characters all encounter problems.

Knowing the structure of a story (or knowing what those poles are that are holding up the tent), can be really helpful.

It can help us understand why an author might have made something really sad happen.

The tent poles I’m talking about here aren’t there in every single story – but you’ll see some form of these tent poles in most of the stories you read.

Knowing Yourself, Knowing Your Kids

First, let’s be clear: there is nothing wrong with you if you get scared or upset when reading sad or scary stories.

God gave you all of your emotions–the happy, cheerful ones, and the sad and scared ones.

When we read, we feel strongly. That’s the way God made us. He designed us to respond to stories. So I’m not here to convince you that you shouldn’t get sad, or that your worry or discomfort is something you need to fix.

We read to live other lives, to visit new places, to travel through time, and yes, to feel deeply. But it’s wise, I think, to know your own limits.

And it’s wise for parents to know this about their kids.

When you feel really strongly as you’re reading a story, you can be grateful that you are fully alive and fully able to be the kind of compassionate, empathetic person who really cares about others.

Looking Beneath the Story…

What I’d like to invite you to do today is look with me at what’s just under the surface of the story.

We’re pulling the fabric back on the tent so we can see the poles that are holding it up.

Knowing how story structure makes a story work can often make those uncomfortable, sad, or scary parts of books a little less overwhelming.

We might just better understand why the author chose to make that terrible thing happen. And we might just see the beauty of the story a bit more clearly when we look at them this way.

What Story Structure (Often) Looks Like

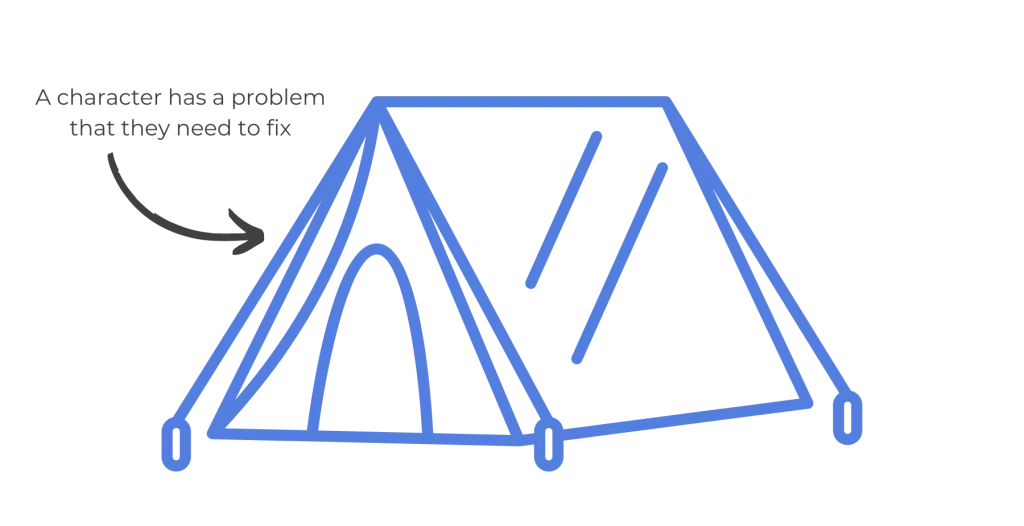

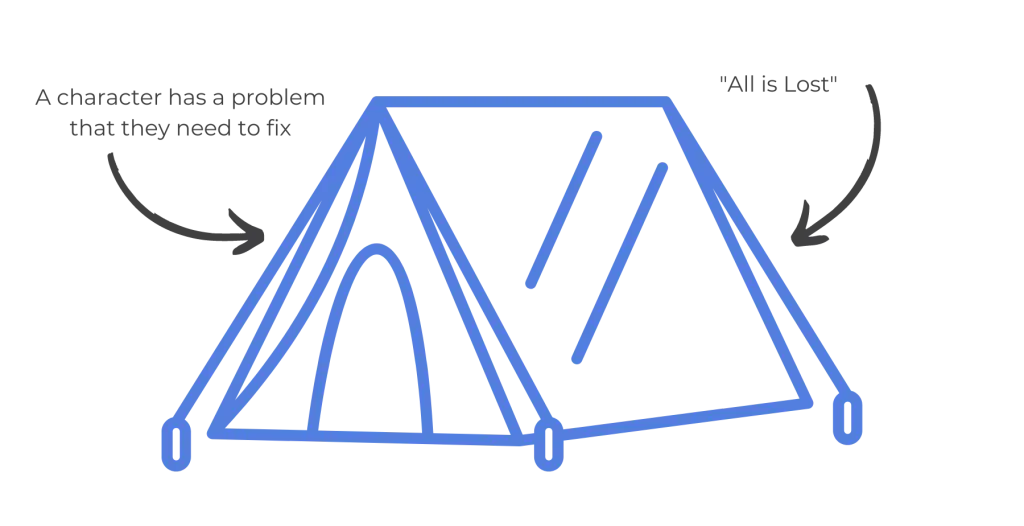

Jonathan Auxier taught a WOW: Writers on Writing Workshop in RAR Premium, and described story structure as these three parts:

- A main character has a problem that they need to fix

- They take steps to solve that problem, and things get worse

- They discover the ultimate solution … and now everything is different

Of course, this is very simplified, but the pattern shows up in most stories that you read, and most movies you watch.

We’ve got a character, and that character has a problem.

If there’s no problem, there’s no story.

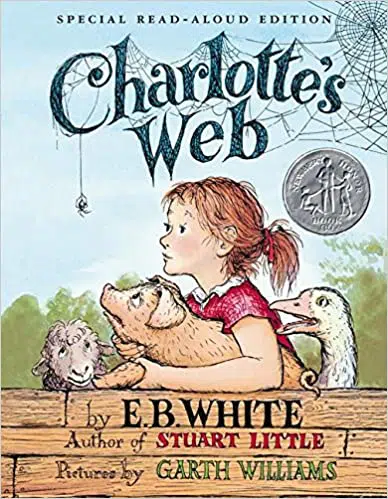

Let’s take a story most of us are probably familiar with: Charlotte’s Web.

Note: there isn’t a good way to talk about the structure of Charlotte’s Web without spoiling the ending. However, if you’re reading this post, you may very well benefit from having the ending spoiled a little before you read it for yourself.

Just know that if you read on, you’ll know how the story ends!

The Tent Poles in Charlotte’s Web

We begin Charlotte’s Web with a pig, Wilbur. He’s the runt of the litter—weak and helpless. Very early in the story, Wilbur discovers that his owners, the Zuckermans, are only keeping him so that they can eat him. (They are farmers, after all.)

On p. 50, Wilbur says quite dramatically:

“I don’t want to die. Save me, somebody! I want to stay alive, right here in my comfortable manure pile.”

His problem, then, is very clear to us: Wilbur wants to live. He wants to be saved.

Aha. This is one of those tent poles: A character has a problem they need to fix.

We know what this character wants: in Wilbur’s case, to live!

Something else is very important here at the beginning. Early in our story, Wilbur asks the other farm animals to play with him. They won’t, though.

“Pigs mean less than nothing to me,” the lamb tells him.

Wilbur is terribly lonely and desperately wants a friend. And he gets one in the spider, Charlotte. Charlotte is not only wonderful, she also promises Wilbur that she won’t let him die.

So now we know what Wilbur fears most: death

And we also know what he loves most: Charlotte

It’s a “take anything else away, but please don’t take away ____” scenario.

Wilbur would probably fill that in with “Charlotte” Please don’t take away Charlotte.

Oooh. This is important.

As soon as we know what the main character wants most and fears most, we can probably predict the hardest thing that’s going to happen in the story.

In fact, we can also predict when it will happen within the story.

“All is Lost”

At the 75% mark, we come to what storytellers often call the “All is Lost” moment.

If we know what the main character most fears will happen, we can almost always guess what’s going to happen at about the 75% mark of the story.

- If the main character most fears losing her favorite backpack, that backpack is going to be nowhere in sight at the 75% mark.

- If the main character most fears moving away from her best friend, the best friend will very likely move away at the 75% mark.

- If the main character most fears deep water, that main character is probably going to find himself in a deep pool or a lake at the 75% mark.

Because at about the 75% mark, the main character has to overcome their greatest fear to get what they most need.

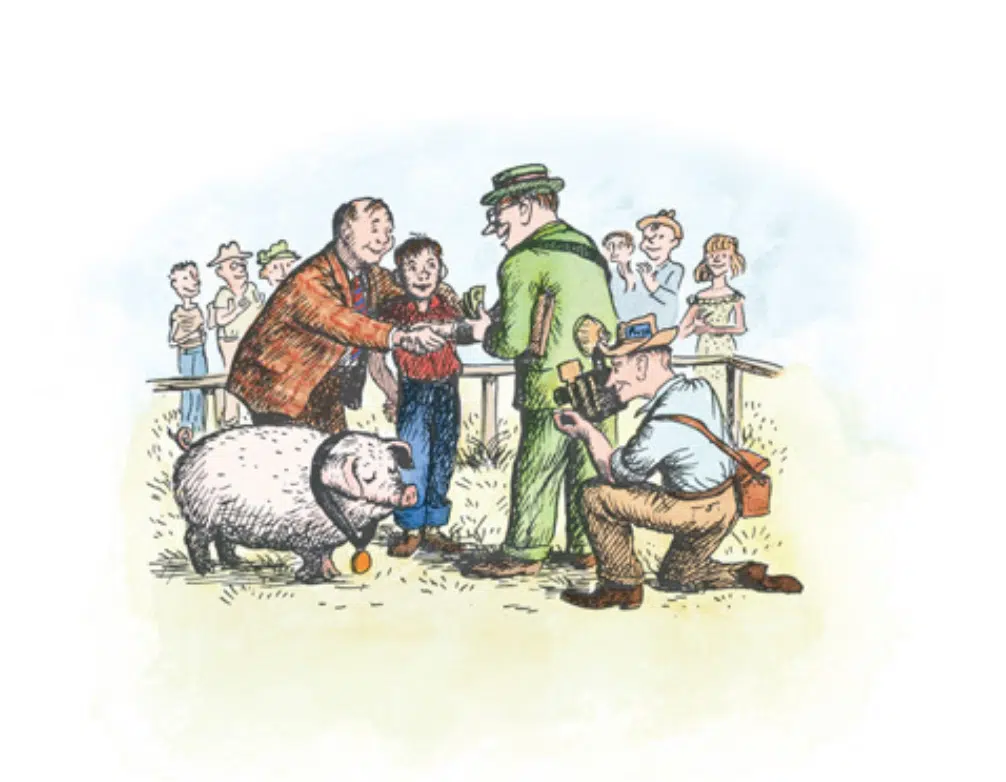

In our example of Charlotte’s Web, we can pretty confident that at about the 75% mark, Wilbur is going to be very close to death, and he might even lose Charlotte.

And in fact, that’s what happens.

Charlotte and Wilbur have tried to save Wilbur’s life by making him win the blue ribbon at the fair. After all, who would slaughter a prize-winning pig, just for bacon? The rat Templeton tells Wilbur has failed in his attempt to stay alive. He hasn’t won the blue ribbon he needed to keep from being slaughtered.

“I noticed a big blue prize on the front of his pen. I guess you’re licked, Wilbur- no one will hang any medal on you.”

So now surely he’ll die, right?

At the end of that chapter, we also see Charlotte’s health fading:

“Charlotte crouched unseen, her front legs encircling her egg sac. Her heart was not beating as strongly as usual and she felt weary and old.”

Now… you know what we said Wilbur loved more than anything. And unfortunately, that often means the character will lose that thing they love more than anything.

In Wilbur’s case, he does lose Charlotte. She has had her babies, and it’s now time for her to die. So Wilbur will be saved, yes—but he loses the thing he loves most, his one and only friend.

This may be one of the saddest literary moments I can think of.

We’re Not Done Yet!

But of course, the story doesn’t end there. There’s still a quarter of the story to go, in fact.

Authors don’t write sad and scary stories or torture their characters just because.

They do it because in a story, the character needs to face their biggest fear in order to become who they need to be.

Stories show us again and again that we can overcome what we fear. That we can keep going, even when something bad happens, and that soon, things might look different, but that’s OK. Sometimes, it’s even better than before.

But our character needs to overcome his weakness. And what was Wilbur’s weakness?

Remember back at the beginning, when he was a dramatic, weak little runt? He threw himself down and cried at bad news, instead of doing anything about it. He wanted to have a friend, but didn’t know how to be one.

So what Wilbur needed was to become strong and determined, and to be a good friend.

Take a Close Look Here

This is one of those tent poles I want you to see. I want you to know it’s there.

Because if you know, when you first start a story, that what a character most fears will likely happen at around the 75% mark in order for them to become who they need to be, then you might not be quite as caught off guard when it does happen.

And even better, you’ll know what the author is up to.

And On Toward Hope…

After Charlotte dies, her babies start hatching from the egg sac, and Wilbur is momentarily elated. Then they do what they were born to do—they fly away on their silk threads to start their lives elsewhere, and Wilbur begs them to stay. Three of them do.

He’s a different pig than he was at the beginning. He’s strong and determined, and knows how to be a good friend (as demonstrated by the careful way he tends to Charlotte’s babies while they are in their egg sac.)

And, as it says at the very end:

Life in the barn was very good—night and day, winter nad summer, spring and fall, dull days and bright days. It was the best place to be, thought Wilbur, this warm delicious cellar, with the garrulous geese, the changing seasons, the heat of the sun, the passage of swallows, the nearness of rats, the sameness of sheep, the love of spiders, the smell of manure, and the glory of everything.”

So we have a character who has a problem, tries different things to fix it, and at the 75% mark, it almost always looks like “all is lost” and that thing the character most fears, he or she loses.

But only so that the story can show the character what they need. Because the story never ends at the 75% mark. They overcome their weaknesses, and life is better than before.

We Can Bear It

What this all means is that by reading a sad story, we get to bear witness to a character overcoming odds and becoming who they need to be to fix the problem they started with.

It can also help because when we get to that sad part – we know it’s not the end.

The character hasn’t become who he/she needs to be yet. They have to overcome their weaknesses.

Kate DiCamillo once wrote about her friend, who read Charlotte’s Web over and over as a child. Kate asked her why she re-read the book so many times. Did she hope if she read it again, things would turn out differently?

‘No,’ she said. ‘It wasn’t that. I kept reading it not because I wanted it to turn out differently or thought that it would turn out differently, but because I knew for a fact that it wasn’t going to turn out differently. I knew that a terrible thing was going to happen, and I also knew that it was going to be okay somehow. I thought that I couldn’t bear it, but then when I read it again, it was all so beautiful. And I found out that I could bear it. That was what the story told me. That was what I needed to hear. That I could bear it somehow.’

And so that’s what a story does. It helps us see that others can face what they think they cannot face.

And so can we.

An Example from Frog & Toad Are Friends:

Have you ever read Frog & Toad’s “A Lost Button?”

In that story, Toad has a problem – he’s lost his button. He wants his button more than anything. Take anything else, but give me my button!

So he spends the story trying to find it (and failing). And at the 75% mark, we really think he’s not going to get that button.

The story says:

Toad put the thin button in his pocket. He was very angry. He jumped up and down and screamed, “The whole world is covered with buttons, and not one of them is mine!”

And then Toad slammed the door.

But that’s not the end, right?

No.

In the end, he DOES get his button. But first, he has to overcome his weakness.

His weakness was that he wasn’t very kind to his friend Frog while they were looking for his button. He valued his button over his friend for the whole first part of the story.

In this story, Toad overcomes his weakness of anger, and even though we don’t think, at the 75% mark, that he’ll ever find his button, he does … in the end.

Very, very sad things can happen here at the “All is Lost”

In a really sad book, the 75% mark may be a point where someone the main character loves more than any other dies. It may be that someone they love moves away.

But calling it the “All is Lost” can help you.

When you name it, you remember what is happening underneath the tent. It has to happen to hold the tent up.

The author knew that what the story needed was for the main character to face the thing he or she was most afraid of happening, in order to become the person he or she needed to become.

The Best Stories Leave Us with Hope

Knowing that at the 75% mark, the main character will face their biggest fear and knowing it won’t end there can help you.

If you know this is what is happening beneath the story, you might just feel a little better about the sad parts. If you know this about a story, it might help you when you get to that sad or scary part of the book.

You can ask yourself: “What is the author doing here? Why did he or she put this in here?”

Because you know that an author, when writing, is often asking himself or herself, “What’s the worst thing that could happen to my character?” and then … THEY MAKE THAT HAPPEN.

I know, authors are the worst. :)

But the best stories, even though they might take us to somewhere really, really sad, leave us in a place of hope.

First we have to watch the character face the thing he thinks he cannot face. Then, we see the character (and hopefully, we see ourselves, in our own real world) in a whole new light. With new eyes.

The characters become who they need to become, and we become who we need to become. Because as Julian of Norwich says:

All will be well, and all will be well, and all manner of things will be well.

Look for the Tent Poles; Look for the Hope

The next time you read a story, see if you can find the tent poles underneath.

Ask yourself at the beginning: what does this character want more than anything? What do they fear more than anything?

So then what might happen at the 75% mark?

And then when you’re at the 75% mark, ask yourself: what weaknesses will the character need to overcome?

Sometimes this can be hard to see while you’re reading, and is much easier to see after you’ve finished.

And remember – it’s OK to not like really sad stories. Even E.B. White cried while narrating the audiobook in a sad part of Charlotte’s Web. In fact, it took him 17 tries to get through recording the saddest part of his book, Charlotte’s Web, for the audiobook.

If you are someone who really doesn’t like very sad stories, there are so many really great stories … read those like crazy.

Also, for parents, go to trusted sources for good stories that leave us with hope like:

And, maybe some day, sad and scary stories will get easier. Maybe just knowing about tent poles will make reading sad books easier!

Whatever you do…

Don’t let the fear of sad or scary books keep you from reading.

Look for the tent poles, look for the hope.

If this is interesting to you, be sure to watch the Storytelling Made Simple Workshop RAR Premium. This is part of our WOW: Writers On Writing series, where kids learn writing techniques from today’s best published authors.

You can find out more at RARpremium.com.

Books mentioned in the show

Links mentioned in the show

You might also like…

- Reading ‘messy’ books about hard topics with kids

- Inputs to nourish the soul

- My kids aren’t good about picking books at the library. What do I do?

More free resources and booklists

Get the best episodes and reources

from the Read-Aloud Revival