Sarah McKenzie (00:00):

When our oldest daughter Audrey was about nine, I wanted to use a method in homeschooling called narration. The idea is simple. You read a short passage to your child from a book and then ask them to tell it back to you in their own words. Here’s what happened though. Every time I told Audrey we’d be doing narration and then read to her, she’d freeze up. I actually think she listened less well to what I was reading when she knew I wanted a narration after. I would read a passage and she would stare as if in pain the whole time. Then I’d ask her to tell it back to me and she’d basically beat an anxious ball of nerves and could remember almost nothing.

(00:42):

I remember one time specifically, I was reading Ethel Pochocki’s Once Upon a Time Saints to all of my kids. They usually loved these stories and they would listen with rapt attention. Then I decided we should do narration of them and be good Charlotte Mason home schoolers. Honestly narration ruined that book for them.

(01:03):

While I knew my girls had been listening carefully and soaking up the stories before I tried to have them narrate, as soon as I added narration to their docket, they froze. Couldn’t do it. The enjoyment of the story, their ability to listen to what the story was actually about just dissolved.

(01:20):

If you’ve been in homeschooling circles for long, you’ve probably heard about the concept of narration. It’s a method most widely associated with Charlotte Mason, who was a British educator in the late 19th, early 20th centuries, who really dedicated her life to improving the quality of children’s education. Home schoolers use her methods a lot, and I’ve gained a lot of wisdom from learning Charlotte Mason methods, or as many of us call it a CM style of education. One of the basic tenets of CM education is indeed narration. It’s sort of Charlotte Mason 1011, honestly. The entire Charlotte Mason methodology rests on this idea of having a child tell back what they just read or what they just heard read to them.

(02:06):

Maybe narration works great in your homeschool and if that is the case, keep on going. I would never tell you to fix something that isn’t broken in your homeschool. But, if your experience with narration has not been super sunshiny, if your kids feel anxious about narration or you notice the quality of their listening decreases when they know you’re going to ask them to tell back what they heard or what they read, I have some ideas for you.

(02:32):

Now that child, I mentioned at the beginning of this episode, the one who basically had a little anxiety attack every time I asked her to narrate, who quit listening when I asked her to narrate. She’s now in English major, a sophomore at college in fact, and her professors keep mentioning to her what an excellent student she is, how well she writes about the rather difficult books they read for their college English classes. So I can attest that narration is not the only way to go about reading and thinking about what you read. There are other options, and that is what I’m presenting in this episode. If you are the kind of homeschooling parent who wants to read with your kids, enjoy them and help them fall head over heels and love with stories. If you’re the kind of homeschooling parent who wants to have lively conversations with your kids, about what you’re reading and use those books to grow closer to each other and to connect, stick around. You are my kind of homeschooler.

(03:32):

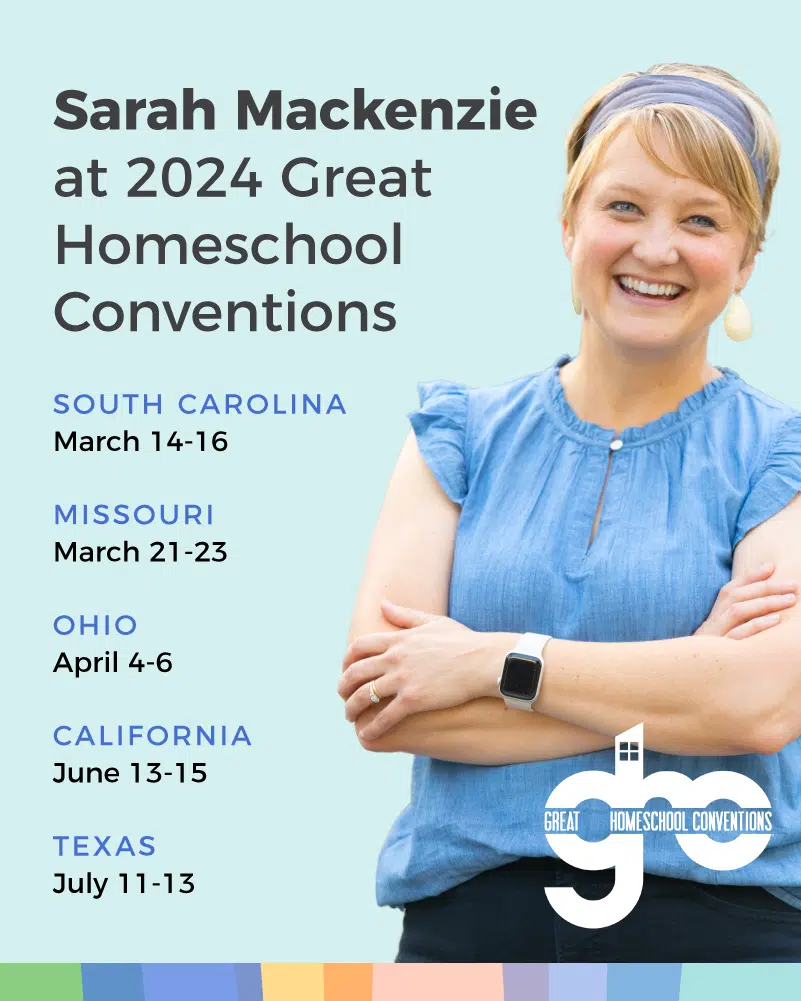

You’re listening to the Read Aloud Revival podcast. I’m your host, Sarah McKenzie, homeschooling mama of six and author of the Read Aloud Family and Teaching From Rest. As parents, we’re overwhelmed with a lot to do. It feels like every child needs something different. The good news is you are the best person to help your kids learn and grow and home is the best place to fall in love with books. This podcast has been downloaded 7 million times in over 160 countries. If you want to nurture warm relationships, while also raising kids who love to read you’re in good company. We’ll help your kids fall in love with books and we’ll help you fall in love with homeschooling. Let’s get started.

(04:23):

What is narration exactly? Like I said in the introduction, the method was popularized by Charlotte Mason. It’s a form of telling back what you’ve read or telling back what’s been read to you. The purpose is generally to help the student synthesize what they’ve read. Usually directions for doing narration with your kids are something like this. They’ll say, read aloud a passage to your child, or have your child read a passage, depending on the age of your child and their abilities. They’ll say only read the passage once and do not read it again. The single reading is a very central part of basic narration, and then ask your child to tell back what they heard in their own words. That’s it. You read a loud a passage or have your child read it, only once not twice, and then ask your child to tell back what they read or what they heard.

(05:16):

Now, it’s worth noting that most proponents of CM education don’t start formal narration at all until after age six. For the first several years after that, all narration are oral. We wouldn’t have your child write any of this down. It wouldn’t be written composition or written work until much later, until after they have a good handle on oral narration, usually until after they’re 10. Usually we’re instructed not to guide the student whatsoever in their response, so tell me back what you heard in your own words is about as much as proponents of narration usually want you to give your kids. No hints or prompts. We’re also often told that the child must do this after a single reading, as rereading a passage will diminish their habit of attention. That’s kind of a basic role in the Charlotte Mason world.

(06:03):

I have so many opinions here, so many opinions, but I want to make it clear that this episode is not an attack on narration. It’s just a proposal of an alternative if narration isn’t a great fit for you. If your kids don’t love it and you don’t love it, I have some ideas on what you could do instead.

(06:21):

We spend a lot of time reading and talking to our kids in our home schools. You’ve got to use books you love and methods that feel natural and enjoyable to you because you are more likely to love your homeschooling life and your kids are also more likely to enjoy their homeschooling life if you use methods that feel natural to your family, to the way that your family interacts with each other, if it feels enjoyable and light and kind of easy. As home schoolers, I think we can get a little dogmatic about our methods. We forget that the methods are just supposed to make our jobs easier and more effective. We can choose a different method if any one of them isn’t a good fit for us because whenever we’re focused on a method, instead of focusing on the child in front of us, we miss the point.

(07:08):

This is something that I experienced for many years the beginning of my homeschooling life, I wanted to be a Charlotte Mason homeschooler or a classical homeschooler. I’d pick a kind and I wanted to be really good at that method. But what happened is I focused on the method instead of focusing on the child in front of me, the image of God in front of me, and that’s missing the entire point. The method is simply a tool.

(07:50):

Let’s talk about that for a second actually. Consider what a tool is. Let’s just say a hammer. You got a hammer? I bet you have a hammer in your house. The hammer is a tool. It doesn’t have value on its own. It’s not beautiful in itself. It’s a tool. The hammer is used for something, it’s used for something more beautiful than itself. You use that hammer to build a deck or hang a picture or repair something. You don’t just put the hammer on your counter to admire. It’s not like I have the hammer and therefore there is more value in my life. The hammer is a tool that helps you build something more beautiful than the hammer itself, right?

(08:32):

In the same way, our methods and our curriculum, they’re tools. They help us build the more beautiful thing. There’s nothing innately beautiful about your curriculum, about your lesson plans or about your methods. They just help us build the more beautiful thing, the education in the hearts and minds of our kids. If our tools aren’t helping us because maybe our child is different than the kids that Charlotte Mason was thinking of when she began teaching teachers to use narration with their students, well surprise, your child is different and we’ll do the best job educating our kids when we educate them as the individual visual images of God that they are, not as though they should fit into a perfect methods mold.

(09:21):

I’m going to be careful here because this is getting awfully close to a soapbox, isn’t it? Let’s talk about the goal of narration, because I think it’s always worthwhile to think about why we’re doing any given thing in our home schools. What’s the purpose? When it comes to narration, a big purpose of it is to synthesize what you’ve read, but there’s actually more to it than that. Proponents of narration and Charlotte Mason’s ideas behind it were to train the habit of attention, which is a hugely important, to help our kids train their habit of attention, to help them make connection and synthesize information on their own. Another purpose of it is as a precursor to written composition because narration is simply oral composition, you’re composing sentences orally. Then once you get the hang of that, then you can translate that into written composition. It’s as a precursor to write and composition.

(10:17):

But think about this. When a teacher says, read this chapter and answer the questions at the end, think about the history books that we always used in the classroom when I was a student were you read the chapter and then you had to answer the questions at the back. Or if you’re thinking of comprehension style questions like, in this story, where did the main character go after he left the library? Or in what year did this story take place? Those are comprehension questions. The teacher does the thinking in all of those cases.

(10:47):

Let’s think about that history chapter. You’ve got a history chapter and you’ve got 10 questions at the end. The person who wrote those questions actually did the bulk of the thinking because they actually were taking the information presented in that section and were making judgements and measurements of what was the most important thing to pull out and then they base their questions around that. What are the important bits? Actually the person who wrote the questions was doing most of the learning and your child is not, they just got left out of a whole bunch of the learning. With the comprehension questions, if you were to say, in what year did this story that you just read take place or in what region did this story take place? Again, the teachers doing the thinking because the teachers thinking through what happened in that chapter or that story and making decisions about what matters most. The teachers actually doing the hardest thinking for the student and this robs our kids of the learning.

(11:41):

This is important to know because this idea of wanting our kids to synthesize information, to be able to train their habit of attention, to make connections and for them to be able to read or listen to something and pull out the most important parts, that’s all really good thinking and those are all really worthy goals. I want all of those for my kids. I want to train their habit of attention. I want them to make connections and synthesize information. I want them to practice oral composition as a precursor to written composition. I want them to do real thinking about the most important things about what they read.

(12:17):

I am on board with all of those goals, but humor me for just a moment. Let’s do something really quick. Take just a minute and think of something you read recently. It can be a chapter of a book, an article. I was going to say a Facebook post, but needs to be something a little bit longer, like a news article. A chapter of a book would be really good. You got something? Just think of it for a second. Okay. Now tell me back what you read in your own words.

(12:52):

What happened in your body when I asked you to do that? Pay attention to that. I did this at RAR Premium recently, and attendees said they felt anxiety. They felt their body stiffing up. They felt a little bit of panic. They felt a little bit of, I don’t know where to start. It feels like a quiz, because I’m sitting here and you’re sitting there and I’m asking you to tell me back what you read and you feel like there’s a right or a wrong answer even if I tell you there’s not.

(13:22):

Now, this has actually amplified this feeling of being a quiz. I think it’s amplified if we’ve both read the same thing. Let’s say that I read to you a chapter from The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, and now I say, tell me back what you just heard. That really feels like a quiz because I’m sitting here and you’re sitting there and we read the same thing. Honestly, if you came over to my house for tea and I read a passage to you from a book I loved lately and then I finished reading it and said, okay, tell me back what you just heard. You’d be like, this a trick, why are you asking me that? This is not how readers communicate. This is not a normal question.

(14:01):

If you came over for tea and I told you “Oh my goodness, I just finished this book. It’s called The Fountains of Silence by Ruta Sepetys and it tells the story of a girl named Anna who works at the Hilton in Madrid, Spain in these years following Spanish Civil War under the dictator Franco’s rule. Anyway, this 18 year old boy and his family come to the hotel because their father is an oil tycoon.” Then I go on to tell you what happens and what I loved about it. That’s normal, right? I’m narrating the book, but it’s natural. It’s normal. It’s normal for me, me to tell you about it because you haven’t read the book. But if you and I both read the book and I started doing that, that’s just weird. It’s not the way adult readers interact with books.

(14:49):

When your sister calls you on the phone or your friend calls you on the phone and tells you about this book, she could not put down, you don’t ask her to tell everything she remembers from it. If we’re raising adult readers, it’s worth considering that what we want them to gain are skills that they’ll use as readers in their adult lives.

(15:17):

Let’s circle back to these goals that we were talking about earlier. Training the habit of attention, making connections and synthesizing information, and then practice with composing words and ideas and making judgment about what’s the most important thing in this story, what are the important bits that I need to pull out to tell you. Considering what you read and how those ideas apply to other ideas you’ve encountered or putting events in order ,recalling details, assembling all of this into sentences and interacting with someone else. Those are all worthwhile things, but there’s a lower pressure way to do this. If your student balks at narrating, or if you cannot stand doing narration in your home school, or if like me, you notice that your child doesn’t do well with narration, doesn’t listen well. Their reading comprehension goes way down. You can do something else because narration is a tool.

(16:15):

There is nothing beautiful about narration itself. It’s just a tool to help us build something more beautiful. The education in the mind and heart of our child, a mind alive with connections and thoughts and ideas. But we only use a tool if it helps us, not if it hinders us. So if narration is not a tool that you enjoy using, or if it’s a tool that doesn’t seem to fit well with your particular kids, you can do something else. You can use a different tool.

(16:48):

The tool that we use at our house are open ended questions and conversation. I ditched the CM style of narration fairly early on when I saw that it was freezing my students up and it wasn’t a natural way for us to interact in our homeschool. It wasn’t a natural way to talk about books. I never do narration in the CM style as an adult reader. We use open-ended questions and conversation. I think discussion and conversation are some of the most powerful tools you have in your homeschooling toolbox. An open-ended question, by the way, is any question you ask that does not have a specifically correct answer. For example, where did this story take place is not open ended. It doesn’t make our kids think too hard. Again, I had to do the harder thinking to pick the question then my child has to in answering it.

(17:46):

We’ll go back to The Fountains of Silence since I already mentioned it, which by the way, was an excellent book that I enjoyed. It’s a YA book. I think I would recommend it for like 15 or 16 and up. I enjoyed it myself. If you like historical fiction, if you like Susan Meisner novels kind of felt a little bit like that to me.

(18:06):

Let’s go back to The Fountains of Silence. Where did the story take place? The story took place in Madrid, Spain. It’s not that hard of a question. I didn’t have to think really that hard. It also has a right or wrong answer so it’s not open ended. Questions like, should the main character have done that? Or what’s something you don’t want to forget from that chapter? Those are open ended questions. Our kids can answer that those questions in any way.

(18:31):

Let’s think of some kids’ books here. If I was going to be reading Little House on the Prairie with my kids, I could then at the end of a chapter, say, what’s something you don’t want to forget? What they have to do, to answer the question of what something you don’t want to forget, is they have to go through in their mind, everything that they heard in order mostly, and really think through what happened and pull out what feels important to them or resonant to them or significant to them in some way. That takes hard thinking. That’s where real thinking takes place, but there’s not a right or wrong answer, so the pressure also comes way down.

(19:10):

In the chapter where good old bulldog Jack gets lost in the river, the thing that you might want to remember is the moment when Jack got lost or the moment when the Ingalls family realized that Jack was lost. The moment that your son might want to remember is the moment when Jack was found, when he came back and how that felt. There’s no right or wrong answer and they have to think through what they read.

(19:35):

If your child can answer that question, you know that they’ve read and understood what they’ve read. The key test is if you already know the answer, it’s not an open-ended question. That’s how you decide. Is this an open-ended question or not? If you know the answer, it’s not an open-ended question.

(19:50):

This is a more focused kind of narration really is what we’re doing. We’re asking our kids to do the work of synthesizing and making connections and thinking about ideas, but we’re also helping them focus it so it doesn’t feel so overwhelming. We’re taking down the barriers of, you could get this right or wrong.

(20:07):

I did a whole episode called what’s the deal with open ended questions? That’s episode 166. I would suggest right after you listen to this episode, go listen to that one and find out more about how this works. Episode 166. What’s the deal with open ended questions? If you are an RAR Premium member, there’s actually a masterclass on this in RAR Premium. Go to the for mama’s section in the library, and then you can take that class on how to discuss books with your kids even if you have not read them yourself, it’s an excellent class. It’s about one hour, I believe, definitely worth your time. If you’re not a member, by the way, you can take that class by joining RAR Premium, by going to RARPremium.com.

(20:52):

One of the tenets of narration that bothers me the most is that we ask this big question. Tell me what you just read or tell me back what you just heard. That can feel really big. If I say, okay, think back to that article or that chapter of a book or that thing that I said, think of something you just recently read. Got it? If I say, “What is something that stuck out to you about that piece? About that chapter? About that essay? About that article?” You could probably answer that. Or if it was a chapter in a book, if I said, “Who do you think showed the most courage in chapter?” You could answer that.

(21:29):

You’ve just read, The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe by C.S. Lewis and I say, “Who do you think showed the most courage in that chapter? Lucy Pevensie? Tell me what was the moment where she showed the most courage.” The other sibling might say, “I don’t think it was Lucy Pevensie. I think it was the fawn. I think the fallen showed the most courage.”

(21:51):

We can have a whole conversation where we’re making connections and synthesizing information and practicing oral composition and considering what we read and how those ideas apply to other ideas we’ve encountered. We’re putting events in order, and we’re recalling details and specifics, and we’re assembling all of this into sentences and interacting with someone else and none of it feels like a quiz because the question was open ended and it feels so much more natural. When my best friend calls me and says, “I just read this book and you’re going to love it” it is very common for me to say, “what did you love about it?” not “Tell me back what the book was about.”

(22:41):

Even better than asking an open-ended question is just to offer up your own answer and basically model answering open-ended questions. Let’s take that who was the most courageous question? We finish a chapter and I might not want to ask my kids that question because it kind of feels schooly and like a quiz if I say, who was the most courageous in that chapter. Instead, after I shut the book, I might go, I think the fawn was the most courageous character in that chapter. Then I can tell them why and then I can say, what do you think? Now that feels more like a conversation and not a quiz. This is what we can do. We can model over and over again. You can finish a chapter or an article or a piece of history that you’ve just read with your kids and say, “You know what’s something I don’t want to forget from that?” Then fill in the blank.

(23:37):

My 16 year old son and I are reading The Screwtape Letters by C.S. Lewis right now. We do this all the time. We’re listening to the audio book. We listen for about 20 minutes and then we stop it. I’ll just say “Gosh, what I don’t want to forget from today is that thing. What about you?” He’ll go, “I think it was this thing.” It’s just become very casual, so low pressure, it’s so enjoyable. It feels completely different than narration felt in my home school.

(24:05):

We have a free guide with five open-ended questions that you can ask a child of any age about any book or that you can use as a prompt like I mentioned, to be a discussion starter, to model what it looks like to think about open-ended questions when you’re reading. That free guide is in a show notes and if you have not grabbed that free guide yet, you definitely want to do that. We have a text option for this one, so you can get it even easier. If you are not at your computer, you can use your phone to get it. You ready? All you need to do is text the word, send, like S E N D, send it to me. Text the word, send to the number 33777. Again, that’s send like, yes Sarah, send it to me, to the number 33777 and that should do it. If it doesn’t work for any reason, or if you don’t have your phone handy, just go grab it in the show notes, that’s readaloudrevival.com/192.

(25:07):

It is a truly fantastic tool and these questions can replace any literature comprehension workbook you’re tempted to buy. You don’t need them. If your child can have a good conversation with you about the book, you know they’ve comprehended it. You don’t need to have them answer any questions at all after they read and I would highly discourage you from asking them to do that. That makes reading feel like school and we don’t want reading to feel like school. It gives you the benefit of narration, which is that you’re not doing the work for them. You’re not doing the thinking for them. You’re making their brain make the connections. You’re having their brain do the work, but in a very friendly, low pressure way. Remember our goal. We want our kids to read and think and make connections and synthesize what they read and all of that happens with an open-ended question, even a very specific one. This feels so much more doable to me than a big question like tell me back what you just read.

(26:14):

Now, I want to zero in on a couple of things that might come up for you here. One is low quality answers. Where you ask your child and they tell you an answer that you’re like, wow, that was it. Great. Who is the most courageous in this story and they say Lucy Pevensie and you say, “What was the most courageous thing she did?” They’re like, “I don’t know.”

(26:32):

The habit of asking questions matters more than the quality of the answers that your child gives. I’m going to say that again because it’s super important. Teaching your child to make a habit of asking questions when they read is way more important than the quality of answers that your child gives. It turns out that the answers are not where the juice is. The juice is in the conversation itself. The juice is in helping our kids develop the practice of asking questions as they read. Of discussing what they read with someone they love.

(27:12):

This is what will empower our kids to be good discerning readers throughout their lives, to read with discernment, because we want our kids to develop the habit of asking question questions as they read. That habit alone, just the habit of asking questions of themselves, will help them become discerning readers. If you get an answer from your child that isn’t all about insightful, don’t worry. Number one, you’re not alone, happens to all of us. Number two, you’re putting in the time.

(27:39):

I often like to remind people about how bamboo grows. Bamboo is pretty incredible and there is a species of bamboo that if I was to give you a seed and you were to plant it, nothing would happen. All you see is a patch of dirt. You have to water that patch of dirt. You have to protect that patch of dirt. Nothing’s happening. Well, you can’t see what’s happening I should say. After five years, nothing. You see nothing for all your labor. The bamboo sprouts. It’s not just a little sprout. That sprout bursts to life and it can grow 80 feet in 6 weeks. From nothing for 5 years to 80 feet in 6 weeks.

(28:22):

This is a metaphor I like to remember in my homeschool a lot. In RAR Premium, if you are a premium member, go watch our mini class on Water Your Bamboo. It’s a circle with Sarah and it’s about this very thing. This is what homeschooling feels like. We are not going to see our results for a while, but what’s happening with bamboo during those five years is that it’s growing a very complex root structure under the Earth. Just like that in our homeschools, we might not see results for a long time, but something is happening beneath the surface that’s going to make a big difference down the road. When we’re building the habit of asking questions about what we read, even if our kids aren’t giving us amazing answers, we’re putting in the time. We’re watering and tending to that bamboo. Just like real bamboo, we’re not going to see results right away, but things are happening underneath the surface. Over time, they’re developing these habits of becoming good discerning readers and that makes a huge difference. Huge difference.

(29:25):

Don’t worry about low quality answers. If you download that guide I talked about earlier, that’s in the show notes at readaloudrevival.com/192. You’ll find some ideas in the guide for what to do if your child is not giving you answers that you’re hoping for or how to spur discussion. A lot of the time, just making the little switch from asking the open ended question to modeling the answer of an open ended question like I mentioned before.

(29:52):

After reading a chapter of Screwtape Letters, instead of asking my son, “What’s something you don’t want to forget?” me starting the conversation by saying “Here’s one thing I don’t want to forget. What about you?” That can a lot of times open fling wide the doors, especially if you make your answer very basic and low bar, because then your child knows Mom’s not expecting me to be a genius right now. She just wants to know what I’m thinking.

(30:35):

The other tenant of narration that I flat out disagree with, with Charlotte Mason narration is that a child should only hear a passage or should only read a passage once before they narrate. Here’s where all of my opinions with a capital O are going to come out. I’m going to agree to disagree with Ms. Mason here.

(30:56):

This idea that Charlotte Mason had about the single reading is that it would train the child’s habit of attention if they knew they could only read it once, but I just don’t think that’s true. If you told me, watch Anne of Green Gables but you’ll only be able to watch it once not twice, I’m not going to watch it better. I might have some low lying anxiety about not being able to revisit it because you can’t watch that movie too many times, right? C.S. Lewis himself said that any book worth reading would be read more than once, that he couldn’t imagine reading any book that was worth reading and only reading it once.

(31:33):

We did a whole episode on the value of re-reading as the best kind of reading. It’s episode 141. You can look for that in your podcast app or in the show notes. The truth is that there is a lot of evidence to the contrary. A lot of evidence we have now that Charlotte Mason didn’t have back in her day, that our best reading is often done in rereading. On a first read, the first time we read a story, our brain wants to know what happens next.

(32:02):

Let’s just go with a chapter. If I’m reading The Hobbit, my brain is reading that book to answer the question, what happens next? I am paying attention to the plot, but I’m missing a lot of the other layers of what’s going on. A lot of the nuanced language, a lot of the more subtle foreshadowing of literary devices that Tolkien is slipping in there. When we’re reading a book or story, I should say for the first time, our brain wants to know what happens next. We’re missing some of the best of it. It’s only on a reread that our brain frees us up to be able to. Now we know what happens next, now we can dive into some of that beautiful language. Now we can notice some of those more subtle literary devices that are tucked in there.

(32:49):

I mentioned that my oldest daughter, the one who retaliated against narration in the early days, she’s now a sophomore in college and an English major. Her English professors will say routinely, read this story twice before you even think about writing your paper on it because if you’ve only read it once you haven’t read it. This reminds me of another English professor. His name is Alan Jacobs. He’s from Baylor University. He wrote lots of books I love. One of them is the Pleasures of Reading in an Age of Distraction. Another one is How to Think. Anyway, he said on an episode of the podcast with me that any time spent reading is time spent training the habit of attention. The truth is that even if your child is rereading something they’ve read before, they’re reading it at a different level. They’re getting new things from it. They’re seeing what they missed the first time. They’re absolutely training their habit of attention.

(33:50):

I think this idea of just reading something once is a place where Charlotte Mason was just wrong. You can’t be right about everything. I’m pretty convinced she wasn’t right about this if I may be so humble.

(34:00):

I want this to be just a reminder, not to let any method or any tool or any philosophy override your own instinct. You are your child’s mother or father so you notice what lights them up, what works for them. What causes them undue angst. We want to keep the curriculum we use, the methods we use in their place, they’re tools. There’s nothing magical about them. There’s nothing magical about narration either.

(34:28):

It’s just a tool. If it’s a tool that works for you and your kids, that’s great. But if not, you don’t need to feel like a failure or a Charlotte Mason dropout, or that your kids are not getting the best homeschool education they could. You are paying attention to your students and what they need and that is what good educators do. Any method, any tool, you make it serve you. You pay attention to your kids. You try to make it work in a way that fits your family, not making your family fit the method. You know your kids, you are the expert. Uses tools, whether that be narration or open-ended questions or something else entirely as they serve you. Use them to help you with your real goal, because your real goal isn’t to do narration or to ask an open-ended question after each book your child reads. Your real goal is to enliven the heart and the mind of your students. You can do that with any tool you like, any tool that works best for you.

(35:26):

Don’t forget to grab your free guide on open-ended questions. You can use that with kids of any age for any book. That’s in the show notes of this episode, readaloudrevival.com/192. It’s also available to you by texting the word, send to the number 33777.

(35:48):

Now it’s time to hear from the kids. They’ll tell us about the books they’ve been loving lately.

(36:05):

What’s your name?

Max (36:07):

Max.

Sarah McKenzie (36:07):

How old are you Max?

Max (36:09):

Two.

Sarah McKenzie (36:10):

Where are you from?

Max (36:11):

Omaha, Nebraska.

Sarah McKenzie (36:13):

What is your favorite book?

Max (36:17):

Strega Nona.

Sarah McKenzie (36:18):

Why do you like Strega Nona?

Max (36:22):

Noodles of noodles.

Bias (36:24):

Hi, I’m Bias and I’m four, and I’m from Omaha, Nebraska. My favorite book is Chicks and Salsa because I like pigs eating chili peppers.

Ellie (36:43):

Hi, my name is Ellie and I’m from Omaha, Nebraska and I’m eight. My favorite series is the Wing Feather saga because it is very funny and I love when my dad reads it to me.

Blaze (36:58):

Hi, my name is Blaze and I’m six years old. I’m from Omaha, Nebraska. My favorite book is Ricky Ticky Tambo because it gives you a lesson to listen to your parents.

Paige (37:17):

Hi, my name is Paige. I’m six and a half years old. I live in Minnesota and my favorite book is The Dollhouse Fairy because it has fairies in it.

Paige 2 (37:29):

Hi, my name’s Paige. I’m six and a half. I live in Minnesota. My favorite book is The Little Gardener. I like it because I really like plants. Goodbye.

Emma (37:46):

My name is Emma. I’m 11 years old and I come from California. My favorite book is Wings of Fire because there’s fantasy, romance and dragons. My favorite character is Peril by far because she says tons of things that are funny.

William (38:02):

My name is William. I’m seven years old. I come from California and my favorite book is Harry Potter and the [inaudible 00:38:10]. I like Harry Potter because it’s a boy who goes on magical adventures of witchcraft and wizardry.

Sarah McKenzie (38:22):

Thank you kids. Don’t forget you can grab your free guide that has five open ended questions you can use with any child and any book of any age. It’s a really versatile tool. It’s absolutely free. Grab it in the show notes, readaloudrevival.com/192, or you can text the word, send to 33777.

(38:45):

If you haven’t yet listen to episode 166 and actually, even if you have, it’s probably been a while since you’ve listened to it, the whole episode about how to use those open ended questions in your family. I’d highly recommend that one. Flip back into your podcast app to find episode 166, or you can just go to readaloudrevival.com/166.

(39:09):

That’s it for me today. Thanks so much for listening. I can’t wait to come back, be here again with you soon. But in the meantime, go make meaningful and lasting connections with your kids through books.